Figuring out fair compensation can be challenging in any environment, but adding equity compensation into the mix can make evaluations even more complex. That’s because the value of stock options and other types of equity compensation can be unclear and unpredictable.

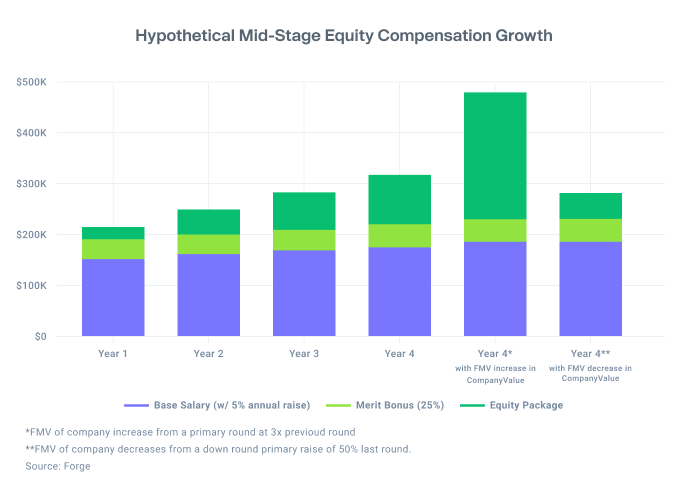

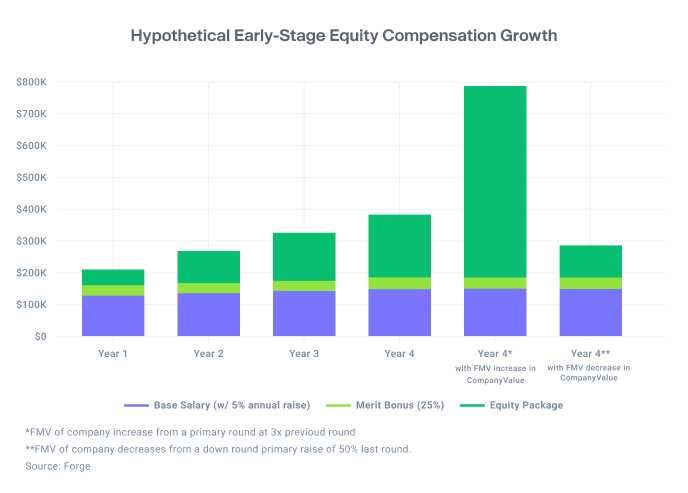

Salaries generally provide consistent paychecks, whereas equity can rise and fall over time. And similarly, initial compensation offers at different companies can lead to vastly different amounts, depending on pay structure and how those businesses grow (or potentially decline) over time, as the charts below exemplify.

The first chart could exemplify a mid-stage startup that offers a higher base salary with less equity, compared with the second example, which might be an early-stage startup. The additional equity in the second example, combined with faster growth, could lead to significantly more pay. However, a down round could mean that you would have come out ahead with a higher base salary, as in the first example.

In other words, compensation offers aren’t always apples-to-apples comparisons, because the starting points don’t always lead to the same ends. Especially at private companies, you might have limited insights into a given company’s growth trajectory and path to liquidity.

You also might lack visibility into what other employees at the company or peers in similar roles elsewhere received in equity compensation. So, you might not know whether you’re getting a fair offer.

However, this information gap is closing.

Resources like Forge have emerged to help prospective employees analyze private companies and get a sense of what their equity might be worth in the future. Other sites like AngelList can also help when it comes to benchmarking equity offers for your job role or location. And by brushing up on your knowledge of how equity compensation works, you can more easily evaluate pay packages.

How does equity compensation work?

Before getting too into the weeds of evaluating equity compensation offers, job seekers should understand how equity compensation works and the different ways they can be paid in stock. Also, since all types of equity compensation come with different tax treatments, it’s very important that you consult with both your employer and your tax advisors about what makes the most sense for your situation.

What is restricted stock?

Restricted stock grants are typically only used at early-stage startups and are reserved for founders and early employees. With restricted stock, you buy the shares for their fair market value (FMV) on the date of grant. Typically, this means you own 100% of the shares on Day 1, but subject to a company right to purchase a number of shares after the day you leave the company that decreases the longer you work for them.

So, if you are joining an early-stage startup where you have more bargaining power as Employee #10 instead of Employee #100, asking for restricted stock may be the best choice for you.

What about stock options and restricted stock units (RSUs)?

As companies mature, they typically shift from granting restricted stock to stock options and then restricted stock units (RSUs). Stock options give you the opportunity to buy shares in the future for a given price, and these also generally follow a vesting schedule.

RSUs are like restricted stock grants where you receive actual stock. However, unlike restricted stock grants, with RSUs you typically don’t own any shares on Day 1 but instead receive shares over time according to a vesting schedule.

RSUs are more often used at publicly traded companies, but you might find a late-stage private company offering them. RSUs can provide more certainty in the sense that even with a decline in share price, your equity can still hold some value, as long as the company doesn’t go to zero.

With stock options, however, there’s no guarantee that you’ll be able to exercise the options for a profit, as the share price might not exceed the exercise price (the amount you pay to turn an option into a share) by the time you can cash them in. So, these different levels of risk might affect how you value different equity compensation offers.

What is the difference between ISOs vs. NSOs?

If you’re offered stock options, it’s also important to evaluate what type of options the employer provides.

Incentive stock options (ISOs) can offer more favorable tax treatment, as employees can avoid federal income tax until they sell their shares. However, this favorable tax treatment comes with more strings attached. Key restrictions include only being available to employees (as opposed to consultants and advisors), needing to be exercised within 3 months after termination of employment, holding period requirements, and limits on how many ISOs you can exercise before the excess are treated as NSOs (and thus lose the favorable ISO tax treatment).

Non-qualified stock options (NSOs) have more flexibility; your company might allow you to transfer these options to others, for example. But NSOs are taxed when exercised.

How does equity compensation fit into your overall pay?

In addition to evaluating how you might be paid in stock, consider how equity compensation fits into your overall compensation. That can include areas like:

- Base salary, e.g., $150,000 per year

- Bonuses, e.g., 25% of your base salary if the company reaches its annual revenue goal

- Paid time off, e.g., 15 days of annual leave

- Retirement contributions, e.g., matching what you put into your retirement accounts up to 3% of your annual salary

- Additional employee benefits, e.g., free daily lunch and 100% of health insurance premiums paid for

Suppose the base salary at another company was $125,000 per year instead of $150,000. However, you had a bonus offer worth up to 50% instead of 25%, as well as 25 days of PTO instead of 15. In that case, you might consider these to be relatively equal pay packages.

All these areas add up, and you can decide how different compensation factors come together to make a fair offer or not.

Equity compensation is another one of these levers within a pay package. If a company offers a relatively low base salary but a large stock option grant, for example, you might be willing to take that offer. But if you’re more risk-averse, you might prefer to have more certainty via a higher base salary and lower equity levels.

How much is equity compensation worth?

The more clarity you have on the financial value of equity compensation, the more easily you can generally evaluate job offers. You might be willing to take a large percentage of your compensation in stock options, but then how do you compare one equity offer to another?

Some of the top ways to evaluate equity compensation include the following:

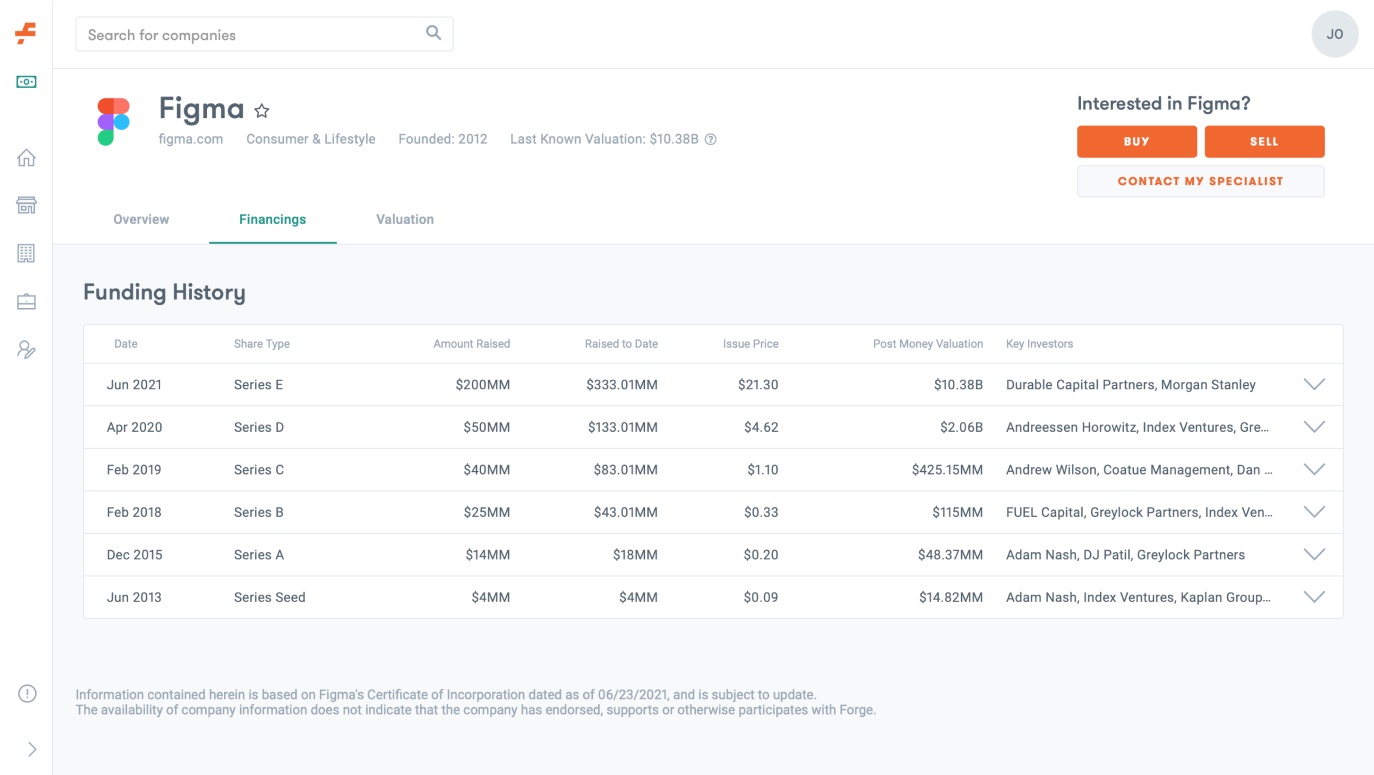

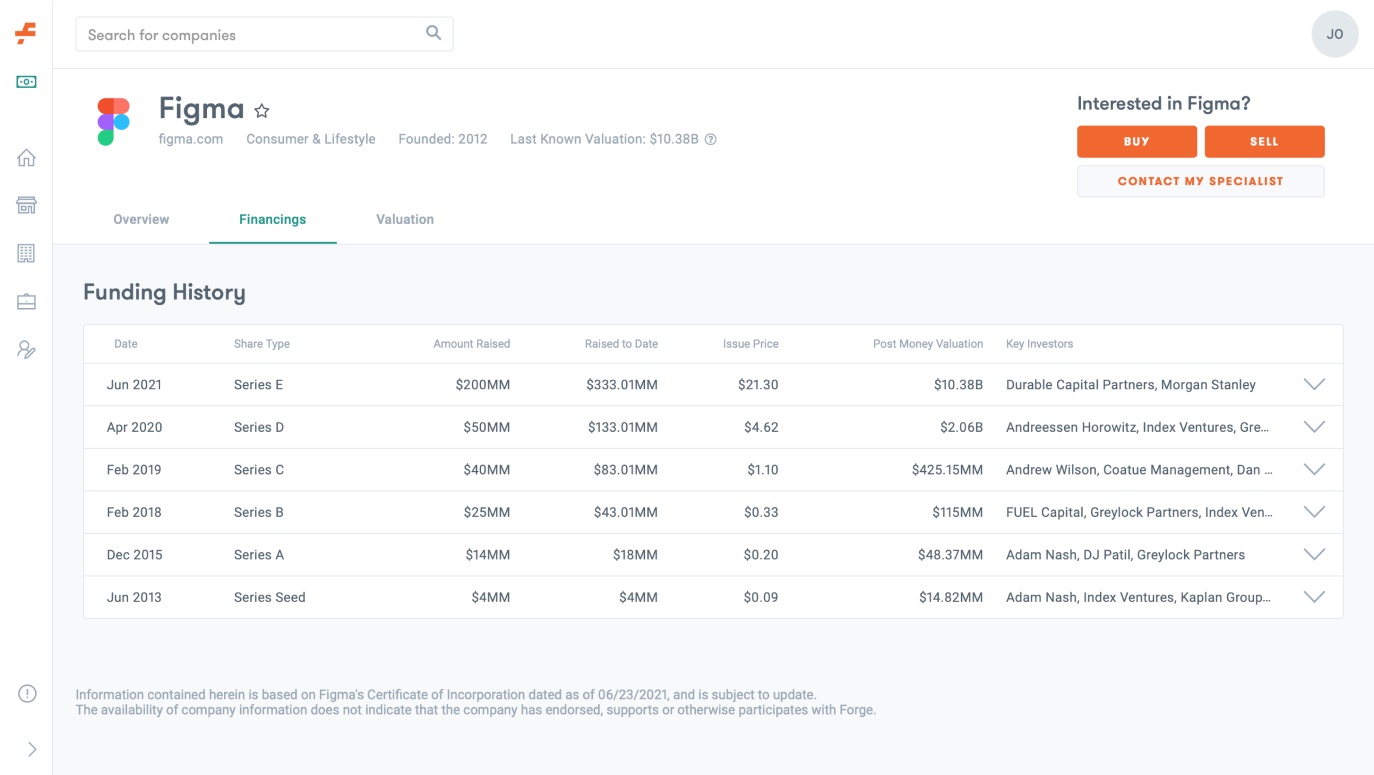

- Review the current valuation of the company or that of competitors, based on data such as recent funding rounds, many of which you can find on Forge. If you find that the company’s valuation is far below that of your exercise price, then the stock options might be worth less than a similar competitor’s offer of stock options at the present fair market value (FMV).

- Assess how similar types of companies' valuations have changed over time. That way, you can calculate what your equity might be worth if your prospective company followed a similar trajectory.

- See what peers have received in terms of equity compensation. Ask friends, look at sites that share compensation data, ask within online groups (assuming you’re not encouraging anyone to break a confidentiality agreement, for example), etc. There’s no guarantee the end values will be the same, but you can at least see if you’re getting comparable opportunities from the outset.

- Consider your outlook for the company in relation to your risk tolerance. You might be willing to take more equity compensation and less guaranteed salary if you’re confident that the company will IPO or have another path to liquidity.

In addition to assessing the overall value of the stock options, consider factors like the vesting schedule and what would happen if you leave the company before exercising your options. Many companies have a 90-day window for you to exercise your options after your departure, but if they have a longer period, that might make the equity compensation more valuable to you, since it gives you more financial flexibility.

By taking these steps and seeing how equity compensation fits into your overall offer, you can more easily determine if you’re getting a fair deal. And the more transparency you have into private market compensation and valuation trends, the better prepared you’ll be to negotiate for more equity compensation.

When it comes to negotiating equity compensation, there’s often information asymmetry between employer and employee. You don’t always know as much as the founders do about company valuation and paths to liquidity, so it can be difficult to know if you’re getting what you’re worth.

But that asymmetry is changing. As we’ll explore in more detail here, job seekers can negotiate many different components of an equity package, which all add up to getting equitable compensation.

What are the components of an equity package?

To figure out how to negotiate equity compensation in a way that maximizes its value to you, consider the different components of an equity offer, such as:

-

Type of equity compensation, e.g., restricted stock units (RSUs) vs. stock options.

This might not be negotiable, but it can inform what seems like a fair value. RSUs generally have less risk than stock options, as RSUs can retain value even when the company’s valuation falls below what it was at the time of the grant. So if you’re getting stock options rather than RSUs, you might try to negotiate for more shares, for instance, to increase your upside potential.

-

Number of shares: The number of shares directly affects how much you stand to gain if the share price increases. 100 shares at $100 per share equal $10,000, whereas 200 shares at $100 per share are worth $20,000. And the number of shares you have, divided by the total number of company shares, gives you your percentage of equity ownership.

So, you might negotiate for a higher number of shares to reach, say, 1% company ownership instead of 0.5%, based on industry benchmarks. And just as importantly, you should try to negotiate your equity as a percentage of the company's fully diluted capitalization instead of outstanding capitalization. Outstanding capitalization = the number of shares that have been issued to date by the company (aka shares outstanding). Meanwhile, fully diluted capitalization = shares outstanding plus shares that are reserved for future issuance but haven't been issued yet by the company (e.g. shares set aside for future employee grants, shares promised to investors through convertible notes, warrants, etc.) In other words, if you only negotiate a percentage based on outstanding capitalization, you could get immediately diluted if the company issues a large amount of equity right after your start date.

-

Fair Market Value (FMV) of the company: This valuation is often used to set your price per share or exercise price. You also can use it to calculate your equity’s value, such as if you know the percentage you’re being offered. Owning 1% of a company valued at $10 million, for example, equals $100,000.

Even though this amount isn’t directly negotiable, it can help you understand the value of an equity offer. A higher valuation than you anticipated, for example, might make you more willing to take a lower equity percentage in the company. Past funding rounds and private market databases like Forge can help you determine valuations.

-

Exercise price: Also known as the strike price, this is what you would pay per share to exercise stock options. For example, an exercise price of $1 per share means that if the company’s valuation reaches $2 per share, you could exercise your options to receive shares worth twice as much as you paid to obtain the shares.

-

Vesting schedule: The vesting schedule sets the timeline for when you own equity or options. If you vest 20% per year, for example, then you might decide to stay with the company for at least five years so you can own 100% of your RSUs or stock options.

While you can try negotiating for a shorter vesting schedule — not because you’re planning to leave the company soon but because you want to decrease risk and cash in sooner — companies might have set policies. If everyone has a five-year vesting schedule, for example, that business might not be willing to set yours at four.

-

Expiration date: You might not be able to sit on your stock options forever. Instead, you might need to exercise them before the expiration date, which might be 10 years or so, before they expire and lose their value.

Also, stock options can expire when you leave a company. That’s often 90 days, meaning you’d have to decide during a short window whether to exercise them, perhaps even before they’ve reached your exercise price.

Here too, there could be some room for more negotiation around a longer expiration date. A company may say they only allow 90 days after separation date, but it’s very common, and easy, for a company to extend this time period. Still, that decision could also be more of a companywide policy that won’t be changed for one person.

How to navigate equity negotiations?

Once you have a solid understanding of the overall value of your equity offer, you can figure out your negotiation approach. Like with salary negotiations, try to keep the conversation based on data and the value that you’d be providing to the company by working there, rather than personal reasons.

Suppose you asked for additional shares because the base salary isn’t enough for you to save for a down payment on a new home. While that might be true, consider how that seems from the employer’s perspective. Why should they do what seems like a favor to you by increasing the equity compensation so you can meet your personal goals?

Instead, consider taking a more market-based approach. For example, if you’re being offered a 0.5% stake in a startup, but your research shows you that similar hires at comparable companies received 1% stakes, you might ask the employer to match that higher amount.

Similarly, you might not want to be as frank as to say that you want a shorter vesting period so you can move on to the next startup sooner. Instead, you might ask how the company arrived at its current vesting schedule and see if the employer would agree to a shorter vesting period to make up for, say, a lack of bonuses that similar companies offer.

You also might point out how a shorter vesting period would align you and the company in terms of growing the company faster so that your shares have more value by the time you can cash them in.

And while you don’t want to take less than what seems like a fair offer, remember that your equity compensation negotiation doesn’t have to end with your hiring.

If an employer doesn’t have much room for negotiation initially, you might agree to revisit the conversation after your first year. While there’s some risk on your part that nothing will change, the upside could be that the company is in a better place the following year to grant additional shares, for example.

Another option could be to work out performance-based equity bonuses. If an employer can’t match cash bonuses that similar companies offer, perhaps they can agree to additional stock grants, such as with each subsequent funding round.

In that case, however, keep stock dilution in mind as the company grows. You can look at databases like Top Startups to get a better sense of what equity grants look like at different funding stages.